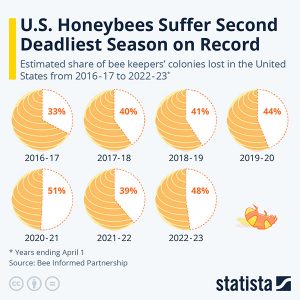

POLLINATOR COLLAPSE: U.S. beekeepers lost an estimated 48% of their honey bee colonies last year

06/29/2023 / By Lance D Johnson

The Bee Informed Partnership recently published their annual Colony Loss and Management Survey, and for the seventh year in a row, the results were grim. According to the survey, the last pollination season was the second most deadly on record for U.S. honeybees. From April 1, 2022 to April 1, 2023, US beekeepers lost an estimated 48.2% of their honey bee colonies. The report includes surveys from small and large-sized operations involving 3,006 US beekeepers who collectively manage 314,360 colonies.

Honey bee population decline spells trouble for US agriculture

To put matters into perspective, the 2020-2021 season saw an estimated 51% decline in honey bee colonies, and the 2021-2022 season saw a 39% drop. As the die-off trend continues, there will be ongoing consequences for agriculture and biodiversity, for honey bees pollinate over 100 different crop types and numerous wild herbs.

“Although the total number of honey bee colonies in the country has remained relatively stable over the last 20 years (~2.6 million colonies according to the USDA NASS Honey Reports), loss rates remain high, indicating that beekeepers are under substantial pressure to recover from losses by creating new colonies every year,” the report authors wrote.

Shortcuts taken in the honey bee industry and in agriculture weaken the bees’ immune systems

The Western honey bee (Apis mellifera L. Hymenoptera: Apidae) is critical to biodiversity and human survival. Loss of honey bee populations impacts the economy, agriculture, and the health of the environment. In the last ten years, some regions of the world have suffered from a significant reduction of honey bee colonies. The honey bee decline in the USA, in many European countries, and in the Middle East has received considerable attention, mostly due to the absence of an easily identifiable cause.

One of the problems stems from the shortcuts taken by the beekeeping industry itself. Bee keepers use corn syrup and other honey substitutes as bee feed; this shortcut contributes to colony collapse by depriving the insects of compounds that strengthen their immune systems. Bees naturally consume their own honey, which contains compounds like p-coumaric acid. This compound helps strengthen a bee’s immune system, helping them ward off the diseases that threaten the colonies.

Due to the way the industry works, bee keepers often take shortcuts to maximize their output of honey into the global market. Commercial beekeepers typically harvest and sell all of the honey produced by the bees. The bees are then given food substitutes like sugar or high-fructose corn syrup, but these products slowly weaken the colonies. A study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences finds that “widespread agricultural use of honey substitutes, including high-fructose corn syrup, may thus compromise the ability of honey bees to cope with pesticides and pathogens and contribute to colony losses.”

To make matters worse, honeybees make contact with many pesticides and herbicides in their daily routine. These pesticides (such as Imidaloprid) harm the honey bees’ immune systems, exhausting their energy, while encouraging the colonization of mites and new viruses that have more resistant traits. For instance, the ectoparasitic mite, Varroa destructor, has been rapidly infesting Apis mellifera and Apis cerana honey bee populations as of late.

According to the Bee Informed Partnership, the most prominent cause of colony death reported by beekeepers over the winter of 2022-23 was “varroa” and its associated viruses. These parasitic mites introduce new viruses with more resilient traits. Varroa destructor made a host shift to the Western honeybee A. mellifera at the beginning of the 20th century and it continues to grow stronger across Europe, the US, Asia, New Zealand, Africa, and the Middle East. These viruses are more likely to take out honey bee pupa because the pupa is undernourished and exposed to chemical toxins that weaken their immune responses.

Sources include:

Submit a correction >>

Tagged Under:

agriculture, biodiversity, economy, environment, food collapse, food supply, harvest, honey bees, Imidaloprid, immunity, mites, parasites, pollination, survival, toxic chemicals, toxins, viral mutations, world agriculture

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

RECENT NEWS & ARTICLES

COPYRIGHT © 2017 FOOD SCIENCE NEWS